Latinos and Chicano/a Artists View History as Instructive to Understanding the Present

“Shek” Vega, “Teenage Angst Has Paid off Well.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is one of the most significant events of the Mexican American experience in the US. The treaty, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the two-year war between the United States and Mexico. The war resulted in a land loss for Mexico totaling 55 percent of the Mexican Republic. The United States acquired 525,000 square miles of Mexican territory, including the land that makes up all or parts of present-day California, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming. Mexico also gave up all claims to Texas dating back to an earlier loss of Texas in 1836. The 1848 treaty guaranteed the civil rights and property of the nearly 100,000 Mexicans living in the acquired territories.

Ana Hernandez Burwell, Untitled. Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The Treaty also resolved earlier unsettled territorial issues. In the aftermath of the Texas Revolution of 1836, Mexico lost 261,000 square miles of territory to the newly formed Republic of Texas, but the boundary between Texas and Mexico was partly unresolved. Although Mexican political leaders did not accept the loss of Texas following the defeat of the Mexican army at San Jacinto in 1836, they conceded in 1848 that Texas was lost and agreed to the Rio Grande as the southern border of Texas and relinquished all claims to Texas. The loss of more than half of its territory, however, contributed to political tensions between the United States and Mexico for years to come.

Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The Ramirez sisters, Manola and Maria, curated this year’s Centro Segundo de Febrero exhibit. The exhibit included works by veteran artists such as Raul Servin and younger artists including “Shek” and Burgundy Woods Rodriguez. Most of the art was completed before the Presidential election of this past November and before Donald Trump’s recent promises of heightened deportation of undocumented workers and their families. Still, perhaps in anticipation of new and increased raids by Immigration Control and Enforcement [ICE], several artists constructed sculptures or created paintings that portrayed the US Border Patrol as agents of a wayward administration.

Manola and Maria Ramirez, “Tradiciones.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

A painting by Sandra Gonzalez touches on the creation of new borders and immigration policies. She portrayed a young woman lying in a field of flowers and maguey plants below the territorial markers of Mexico and the United States. The US marker has a plaque with the text “Immigration Reform and Control Act 1986” while the Mexican marker only has “Presa Falcon” written on the plaque. The Presa Falcon is a South Texas water reservoir built in the 1950s by damming the Rio Grande. The Falcon Dam created a large lake that both the US and Mexico share. The sharing of water has been a contentious issue between the two countries for the past 150 years.

Sandra Gonzalez, “De La Frontera.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

A mixed media work by Allison Villarreal places a howling coyote in its center surrounded by desert plants and flowers. A stream or river rises above the coyote and a toad or salamander and shark lurk nearby. The coyote is often a symbol of wildlife but also represents danger. Immigrants seeking refuge in the United States are often the victims of “coyotes” or smugglers who guide people across the Rio Grande or across the dangerous desert routes of New Mexico and Arizona.

Allison Villarreal, “Dreams of Nostalgia.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

“Shek” Vega, who prefers being referred to as just Shek, is well known in the San Antonio art community for his more than 50 vibrant murals in different parts of the city. In his painting a heavy chain encircles the work enclosing different Mexican iconic images including the halo identified with the Virgin de Guadalupe. Outstretched hands with open wounds on the two palms showing pain and despair also have religious connotations. Shek explained that at an early age he began to question “subjects of authority, patriotism, history, pop culture, and religion.”

Shek. Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

In the top center of his painting Shek placed the words “ANTI” in capital letters above a partial rendering of the American flag and an upside down Alamo shrine. He noted that punk and alternative rock music also influenced him “to be ‘anti’ before being submissive.” Shek believes that to be Chicano “is to forge your own identity through the struggle of multicultural influences and in an effort to find peace in not just the physical world, but the world you create within. Brown pride starts inside.”

Ashley Mireles, “Urban Ecology.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

In Ashley Mireles’s piece, “Urban Ecology,” the artist is depicted as a young person making her first communion in West Texas. In her portrait she is surrounded by factual and fictional stories. Mireles explained that the ink-on-paper drawing merges symbols of Mexican and Texas cultural heritage. On the left, she placed a young doe and coyote in a Texas setting opposite each other. A rattlesnake is placed near a rabbit that is perhaps unaware of its dangerous situation. Mireles pointed out that “These compositions reveal clashes, and double meaning, and contrasting perspectives–one person’s hero is another’s villain.”

Mauro de La Tierra, “La Migra.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 had devastating economic and political impacts on Mexico. Two weeks after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo prospectors discovered gold in California. At the height of the Gold Rush era [1848-1855] an estimated 370 metric tons worth of gold were extracted from Northern California streams and mines. The new boundaries also separated Mexican Americans and Native Americans from portions of their native lands. The war weakened Mexico politically, resulting in the 1860s domination by the Austrian Emperor supported by the French Monarchy. Additional wars and the Mexican Revolution followed. History proved once again to be complicated and consequential.

Burgundy Woods Rodriguez, “Do I Deserve to be in this Show?” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The San Antonio Centro Cultural Aztlan has called upon Latino artists over the past 48 years to use their artistic talents to remind us of the significance of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the ways this treaty has affected the US-Mexico relationship and the lives of Mexicans in both the US and Mexico. Manola and Maria Ramirez, talented artists themselves, have curated an impressive exhibit of works by gifted San Antonio Latino artists. The Segundo de Febrero exhibit closes on February 27th. The Centro is located at 1800 Fredericksburg Road and is open weekdays from 10am to 4pm.

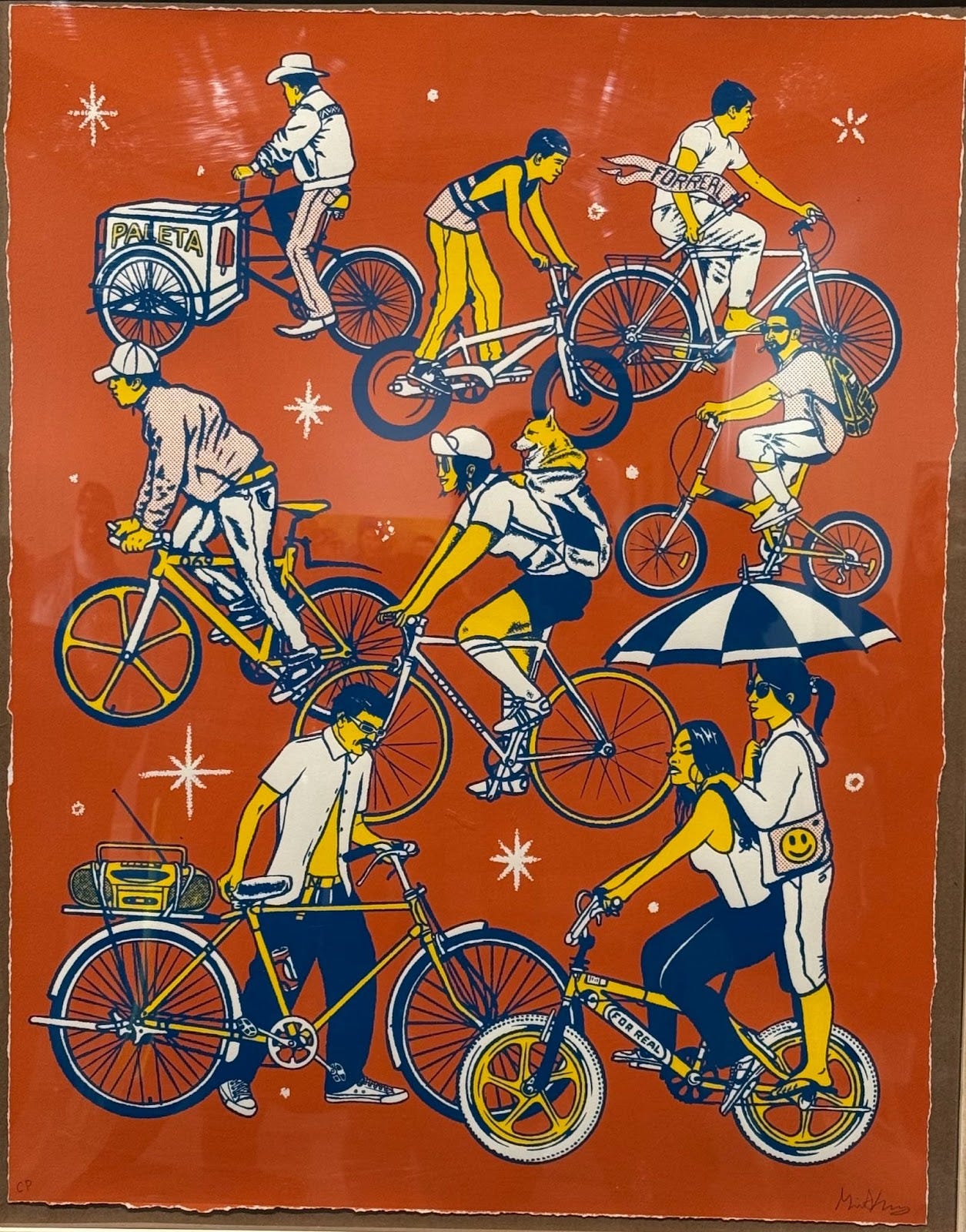

Gilbert Martinez, “Passerby.” Courtesy of the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

_______________________________________________________

Copyright 2025 by Ricardo Romo.