Salomón Huerta: A Visionary Interpreter of Latino Art

Salomón Huerta, a Los Angeles-based painter and printmaker, is known for his enigmatic portraits and compelling depictions of domestic and suburban architecture reflecting his Mexican American heritage and upbringing in Boyle Heights. Over the past quarter-century, Huerta’s works have been acquired by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

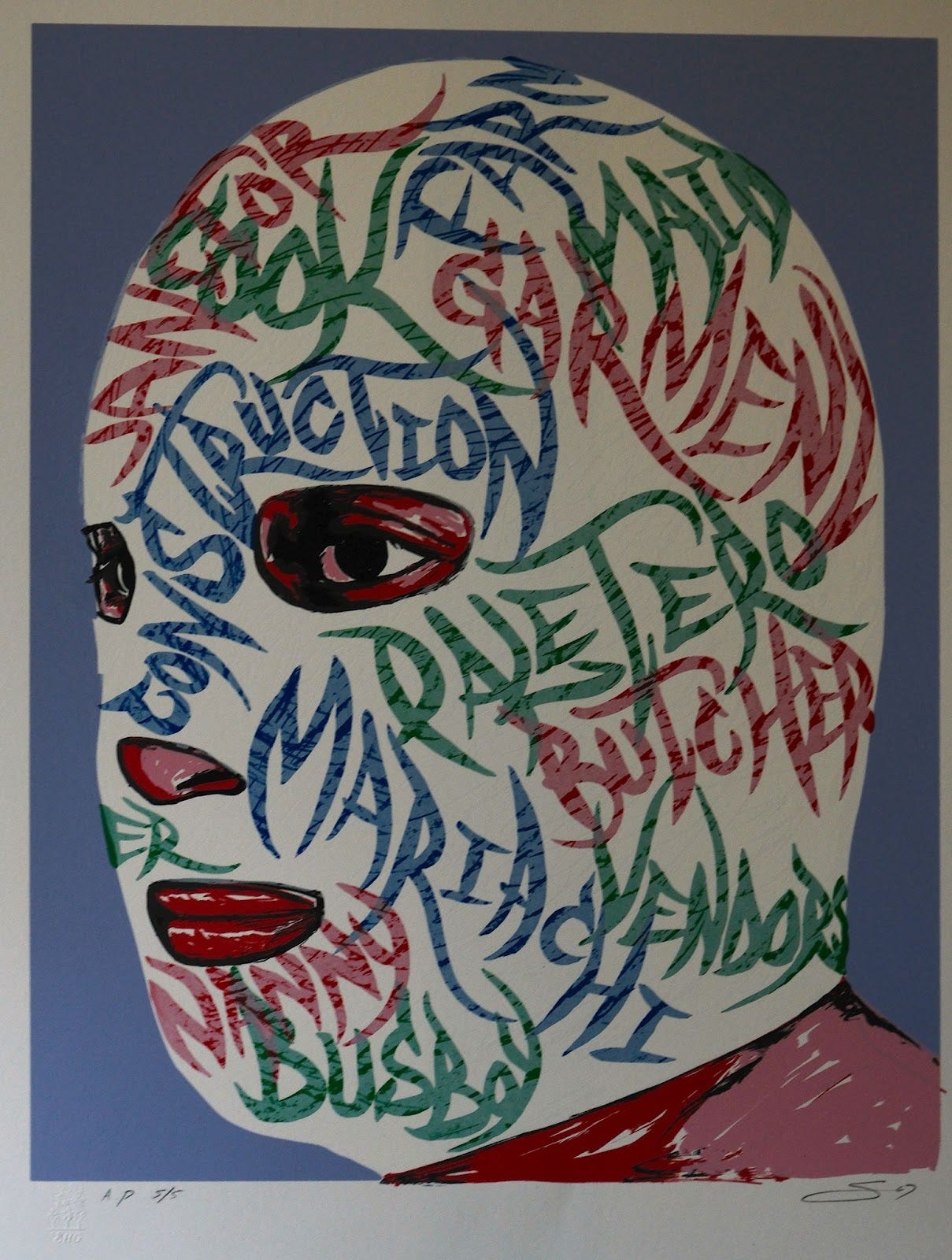

Salomón Huerta, oil painting. Luchador series. Courtesy of the artist.

Born in 1965, Huerta moved to Southern California at age four and grew up in the Boyle Heights/Ramona Gardens area of Los Angeles. When Huerta moved to Boyle Heights in the late 1960s, the area was undergoing an economic and social transformation. From the 1970s through the 1980s, Boyle Heights experienced a steady decline of local industrial jobs that had sustained earlier generations, particularly the shutdown of auto assembly plants and other heavy industries. This economic shift forced residents into low-paying, non-unionized jobs, often in sweatshop textile production or informal sectors, reflecting a broader regional trend of deindustrialization and economic restructuring in East Los Angeles.

Salomón Huerta, oil painting. “Ramona Gardens Homegirl” series. Courtesy of the artist.

The Ramona Gardens public housing project, where Huerta grew up, experienced intense gang violence through the 1980s and early 1990s, becoming known as one of the gang epicenters in Los Angeles. This was exacerbated by increased poverty, high dropout rates among youth, and aggressive policing policies focused on zero tolerance and incarceration. Huerta’s art skills provided a path for him to attend college: his art training includes a BFA from Art Center College of Design (1991) and an MFA from UCLA (1998). Huerta’s family history and early life in Los Angeles significantly inform his creative work that draws on vivid memories of urban life and social dynamics.

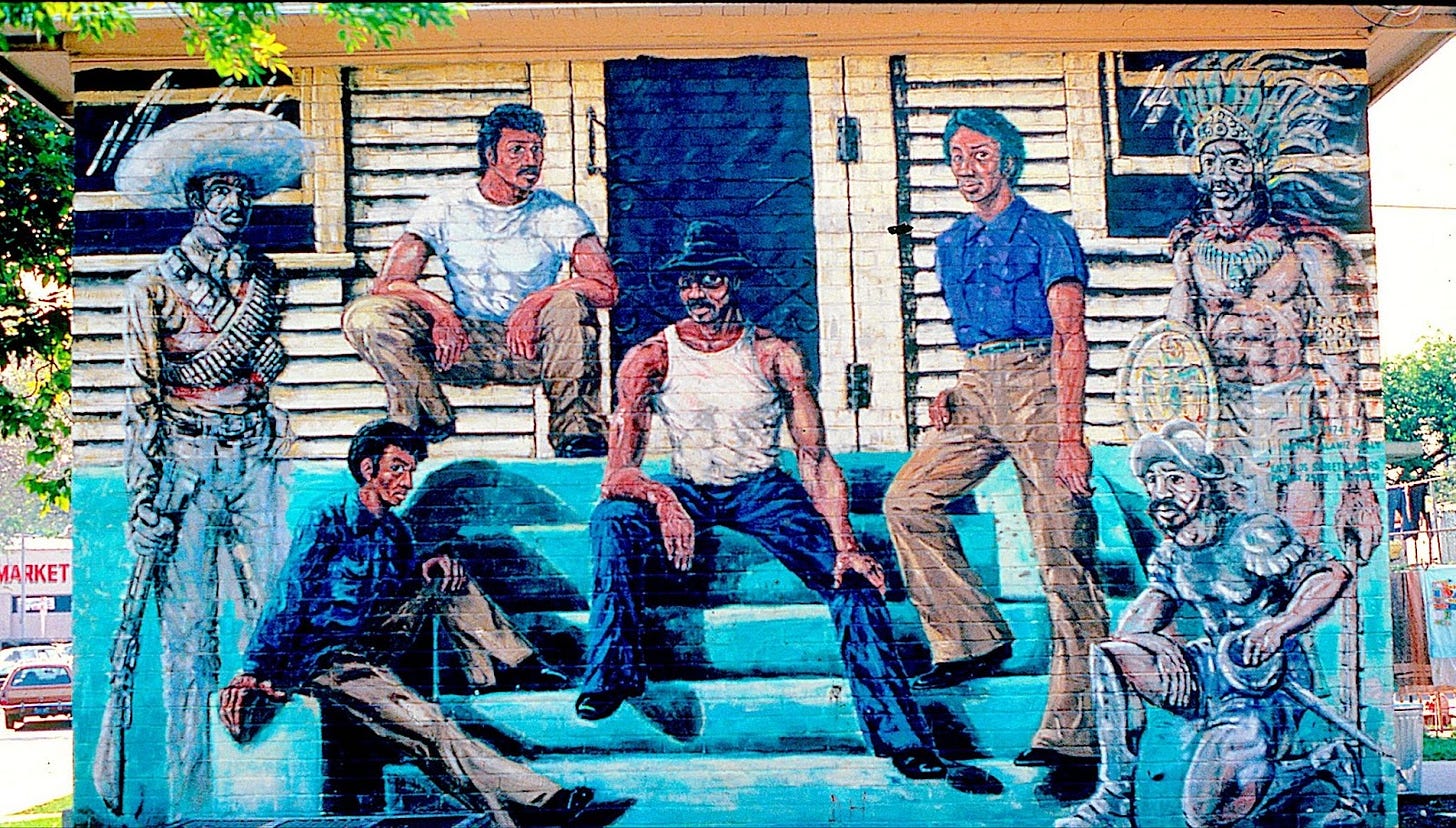

Ramona Gardens Mural by East Los Angeles Streetscapers. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

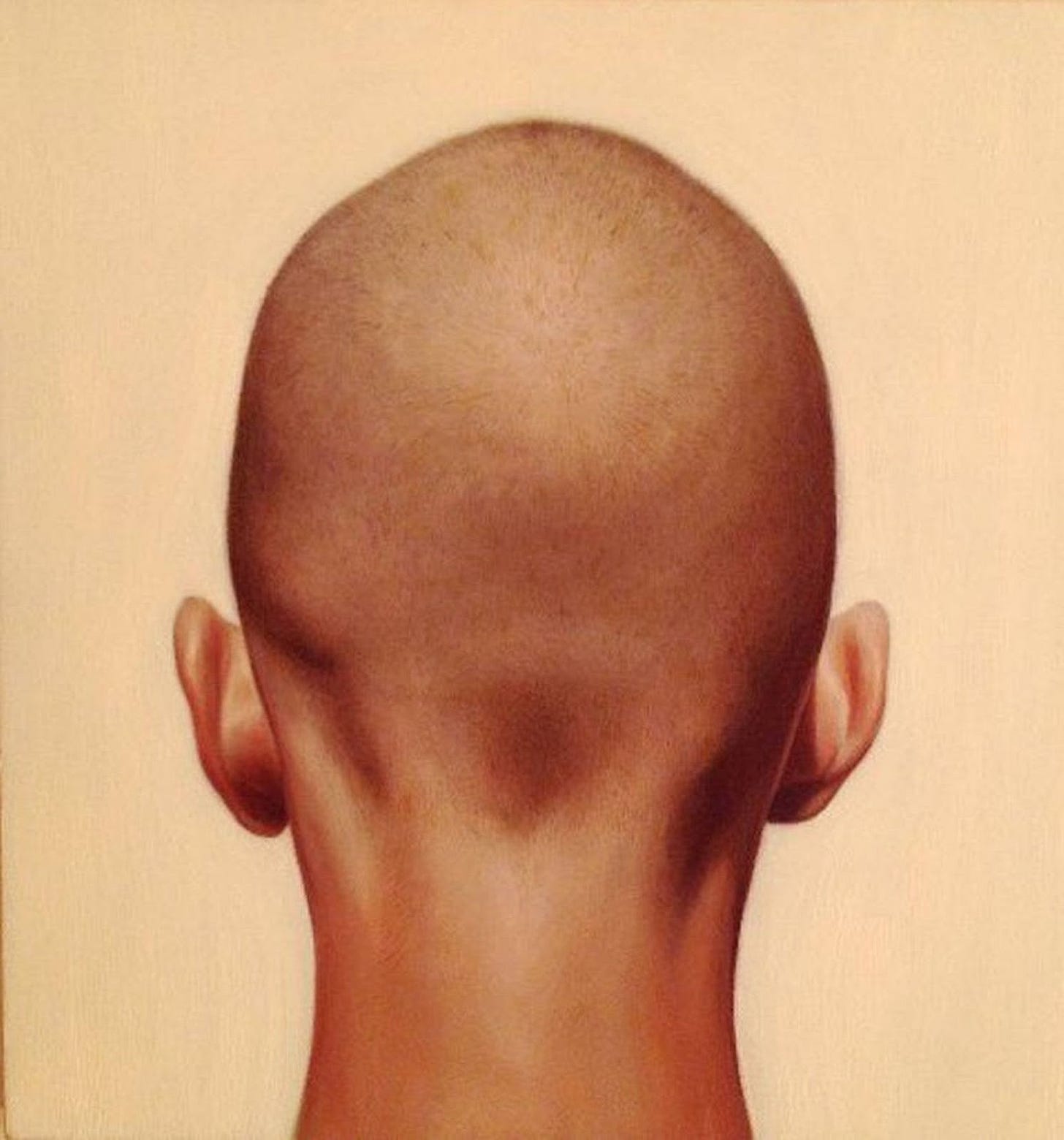

Huerta is best known for his distinctive portraits, often depicting subjects from behind, rendered with meticulous technique and placed against bold, glossy backgrounds. Reviewers emphasize Huerta’s methodical portraiture—particularly the motif of painting subjects from the back, which challenges conventional notions of identity and representation. Huerta’s portraits of shaved heads stood out for their originality. His work expressed both the personal and the universal, offering a new perspective on preconceived ideas and racial profiling.

Los Angeles artist and master printer Richard Duardo introduced us to Huerta 15 years ago when Huerta was living in the San Fernando Valley. Harriett and I visited his home studio, and there we first saw Huerta’s luchadores (Mexican wrestlers known for their colorful masks) and his back-of-the-head profiles. We learned that Huerta had developed the luchadores series as a continuation of his earlier “Back of the Head” portrait works. These wrestler paintings portray a more abstract style of identity where the masks and faces underneath are depicted but intentionally obscured to create ambiguity and abstraction in the imagery.

Salomón Huerta, “Back of the Head” series. Collection of Harriett and Ricardo Romo.

The “Back of the Head” images created by Huerta have a complex origin and explanation. Huerta told reporter Zach Davidson of the Los Angeles Times that “the paintings of the back of the heads were about me challenging myself on portraiture. I wanted to create something that wasn’t stereotypical—something that was universal—with no clear identity.” In a recent interview with Jesús S. Treviño, of Latinopia [August, 2025], Huerta elaborated on how he reached his decision to paint differently, noting that he said to himself: “I’m a figurative painter, I want to do a portrait, a kind of portrait that hasn’t been seen before. I want to do something different beyond the Chicano community, like in the mainstream art world. So that’s where it came about.”

The eminent art magazine Art in America explains Huerta’s shift to painting the backs of his subjects as a conscious strategy to challenge traditional portraiture and the viewer’s assumptions about identity. By eliminating facial features and depicting anonymous figures from behind, Huerta intentionally masks each subject’s identity while preserving subtle clues, such as skin tone and hairstyle. This move, according to Art in America, forces viewers to engage with the portrait based on their own perceptions, biases, and experiences—creating a “vacuum” that the viewers must fill rather than immediately categorizing the sitter’s ethnicity, personality, or social class.

Salomón Huerta, “Luchador” series. Collection of Harriett and Ricardo Romo.

A Los Angeles Times article by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp highlighted Huerta’s unique approach to portraiture in which he creates a sense of detachment and anonymity. [October 8, 2000]. Huerta’s work, Drohojowska-Philp commented, is noted for “its cool, precise realism combined with jewel-tone color backgrounds.” The Drohojowska-Philp article also discussed Huerta’s avoidance of traditional facial expressions, inviting viewers to seek different connections and emphasizing a more abstract, color-focused approach while disguising both his subjects and himself.

Salomón Huerta, “Back of the Head” series. Courtesy of the artist.

Toro Castaño, an independent curatorial researcher and art historian based in Long Beach, California, focuses on visual culture and postmodern forms. He concluded that Huerta’s early works “are a syncretic blend of classical painting techniques, modernist composition, and a commitment to the Cholo aesthetic of East L.A.” Former Director of USC’s Graduate Fine Arts program, Josh Kun, buillt on this descriptive term to articulate post-Chicano artists “as engaging in a negotiation between tradition and change rather than discarding tradition outright.”

I found the “The New Latin Cool” article on the digital Artnet, which highlighted Salomon Huerta’s unconventional approach to portraiture, quite revealing. Huerta’s paintings, noted Artnet, recall bright palettes and streamlined compositions reminiscent of modern painters. By eliminating facial features and cultural markers, Huerta “creates a vacuum that compels viewers to project their own perceptions and biases onto his subjects.” As part of the “New Latin Cool,” Huerta’s work explores “identity from racial, social, and cultural perspectives, questioning stereotypes and the viewer’s role in assigning identity.”

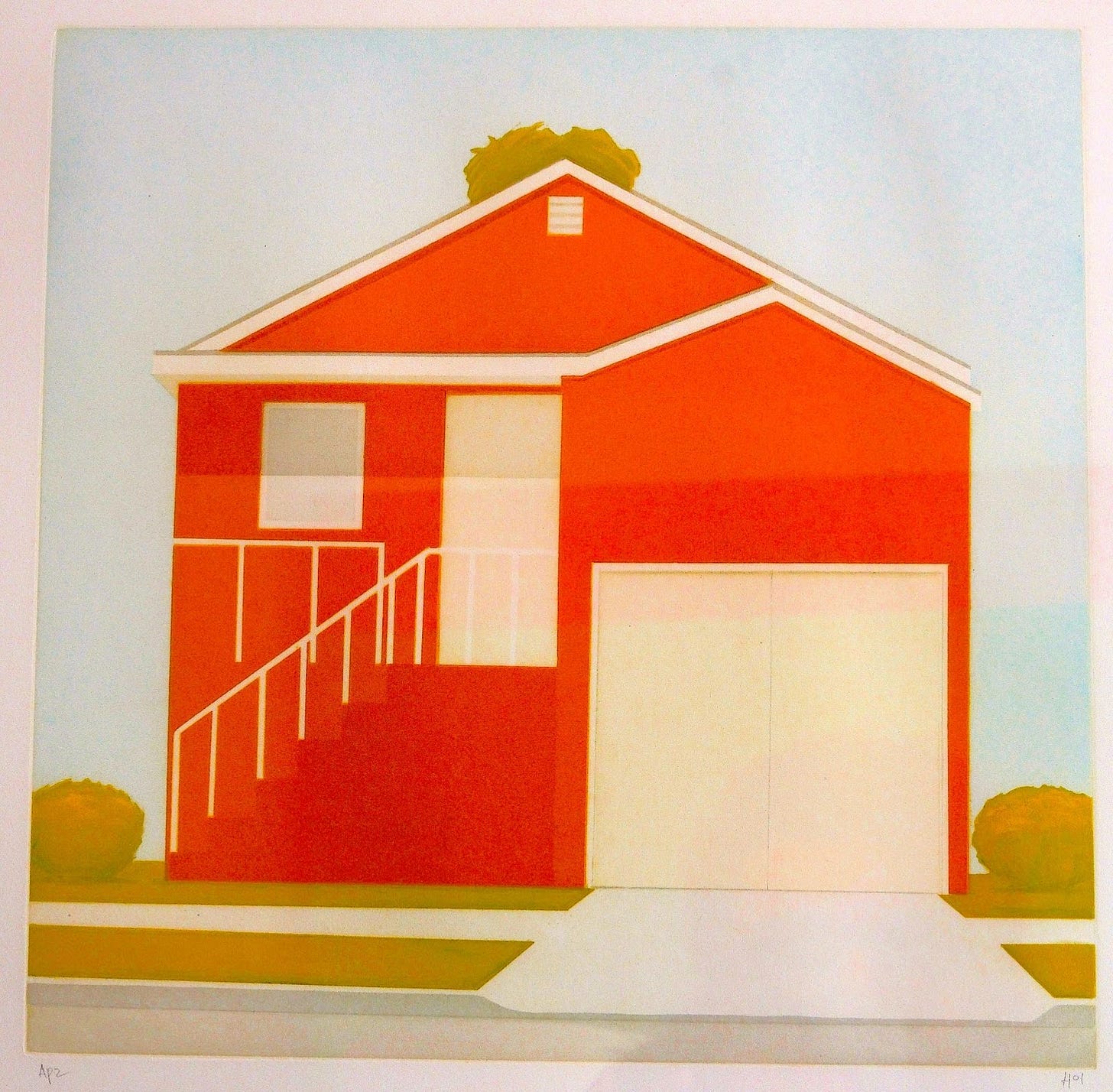

Salomón Huerta, “Home” series. Collection of Harriett and Ricardo Romo.

Huerta’s other well-known artworks include architectural and home scenes. His paintings of modest homes critique social concepts of beauty and class structure. These works are often inspired by landscapes and broader cultural settings from the Los Angeles neighborhoods most familiar to him.

Salomón Huerta, “Home” series. Courtesy of the artist.

David Pagel of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Huerta’s portraits of homes were “ruthless but warm.” Pagel noticed that compared with an earlier period, the images of lower-middle-class houses that Huerta had been painting in oil on canvas or panel had increased in size. According to Pagel, Huerta first depicted snug bungalows and tidy tract homes, all realistically rendered to create the impression that viewers were standing curbside or perhaps passing by in a slow-moving car. As Huera added second stories, porches, and garages to his modest homes, Pagel observed, the streets that ran parallel to the pictures’ lower edges disappeared. The square footage of the lots grew, first gradually and then dramatically.

Salomón Huerta, “Home” series. Courtesy of the artist.

On January 7, 2025, a catastrophic wildfire tore through Southern California, primarily impacting Los Angeles County and the foothill communities of Altadena and Pasadena. Known as The Eaton Fire, this blaze ranked as one of the deadliest and most destructive wildfires in California history. Huerta was painting in his Westwood studio that day when he received an urgent call from his wife, Ana Morales-Huerta, alerting him that the fire was approaching their Pasadena home.

The fire roared, driven by powerful Santa Ana winds gusting up to 100 mph and fueled by eight months of extreme drought and measurable rainfall. Only a few hours after the fire broke out, flames rapidly moved into urban neighborhoods at the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. Over 52,000 residents and more than 20,000 structures were threatened by the fire, and more than 100,000 people were evacuated. The Huertas evacuated at 9 p.m., prioritizing items of immediate value and necessity and only what they could carry in two cars. By 3 a.m., the Eaton Fire destroyed their home.

The Eaton Fire became fully contained on January 31 after burning for 24 days. Over 9,000 buildings, including historic homes and landmarks in Altadena, were destroyed. Since the fire, Huerta and his artist wife, Ana Morales-Huerta, have been actively selling art online to raise funds for subsistence, continuing to work in portraiture and representational painting. Major arts institutions in Los Angeles raised $12 million in aid for artists affected by the wildfires, and efforts to support artists and community members continue. Courageous Latino artists like Salomón Huerta and his wife Ana, who lost their homes and many of their cherished paintings, continue their creative interpretations of Latino experiences.

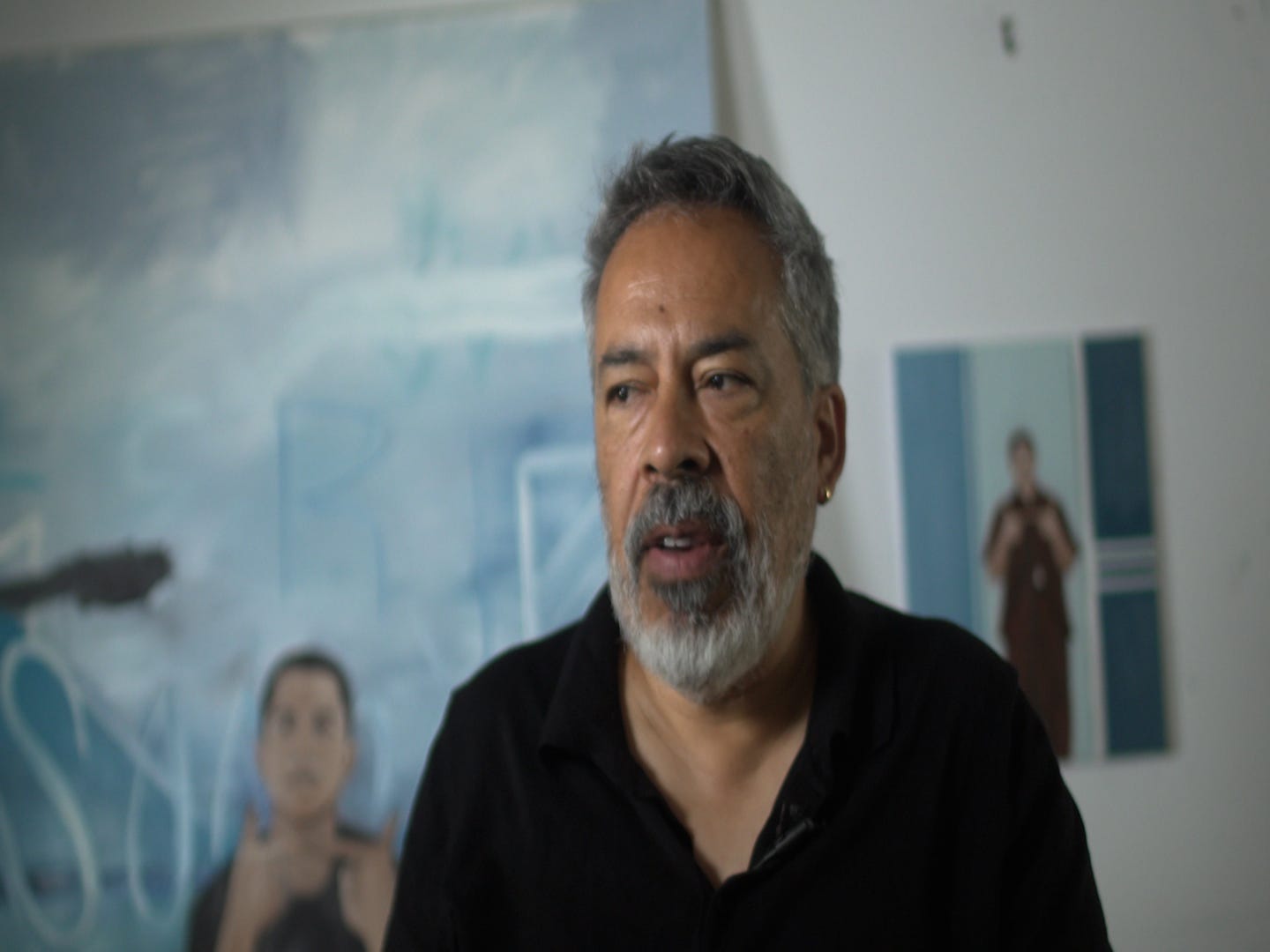

Salomón Huerta. Photo by Jesús S. Treviño.

________________________________________________________________________

Copyright 2025 by Ricardo Romo. All photo credits as noted above.